(This is a repost of the original blog. Check the original blog with this link)

At Chalmers, I discovered how powerful curiosity can be. Whether it was a lively discussion with a professor or guidance from a TA, every interaction felt like an opportunity to explore deeper. The motivation-driven teaching style made learning exciting—I wasn’t just absorbing facts; I was actively connecting with the material with engineering practice. This experience didn’t just help me understand things better; it changed how I approach problems, making me more curious, critical, and creative than ever before.

A Story

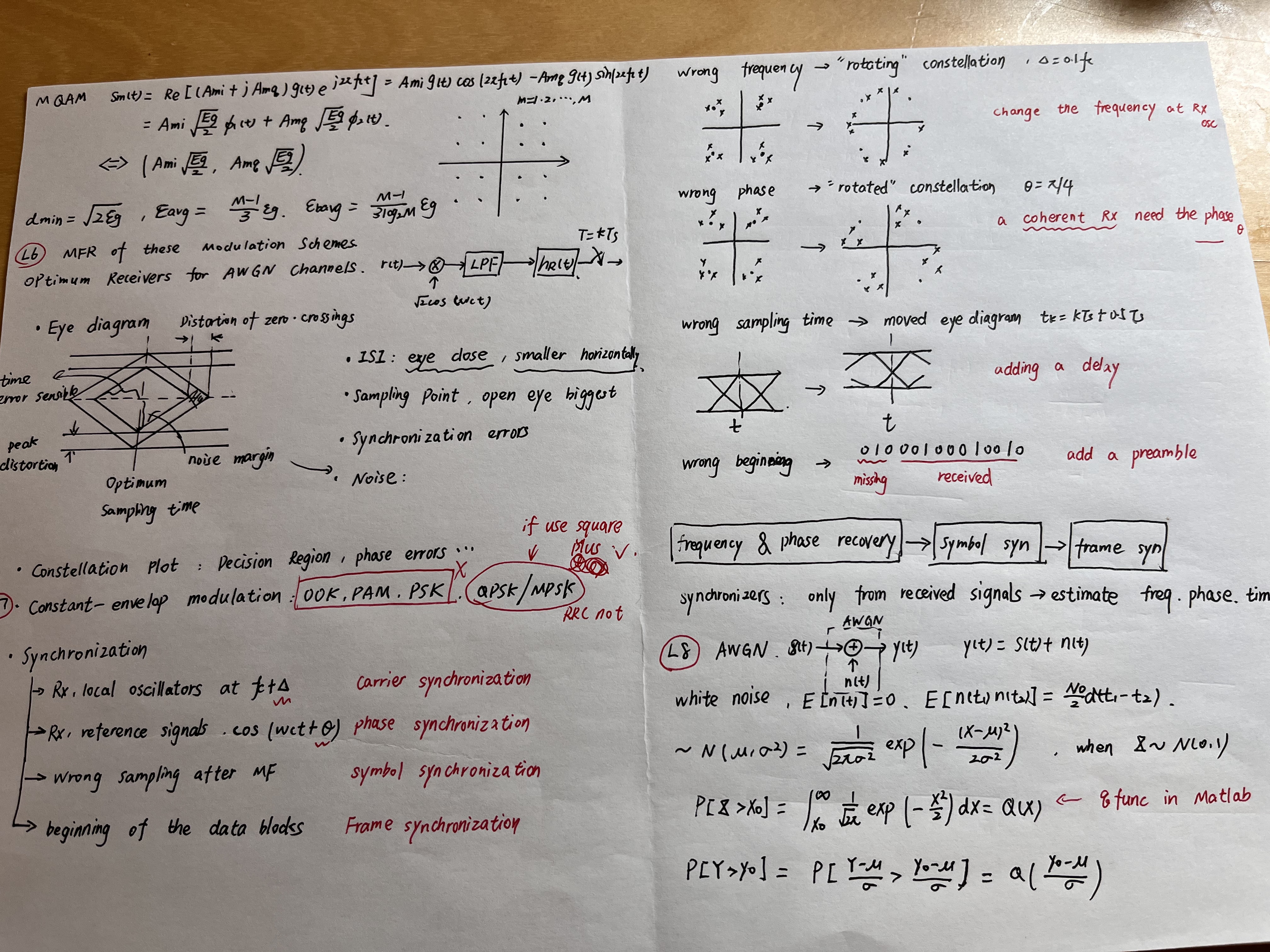

I remember an ordinary afternoon in October, when I felt that the daylight in Sweden still lingered long, and the sky was vividly blue, as if carefully painted by divine hands. I had a question—one that had perplexed me for a long time despite being fundamentally basic. It concerned the definition of energy in signal constellation diagrams, and I decided to bring it to my Introduction to Communication Engineering course professor, Fredrik Brännström.

Before asking my question, I felt somewhat awkward—it was such an elementary question, akin to not understanding the definition of a limit while studying calculus. If I were to use a daily life analogy, it was like wondering why one needs a cup while walking to fetch water. I worried that Fredrik might dismiss my question as trivial, but to my surprise, he looked me in the eye and thoughtfully explained the question from multiple angles. He even offered various intuitive ways to approach the concept, leaving me enlightened.

To be honest, I had never seriously thought about the detailed aspects of these concepts before. Fredrik’s response sparked an even greater desire within me to explore the question further—it felt like something had truly struck a chord deep inside me.

As Fredrik explained, “Different authors have their own conventions when writing textbooks. There’s no right or wrong—it’s about understanding their motivation. This will deepen your understanding and reveal their underlying unity. This is a very fundamental question.” His words left a lasting impression on me. I kept on thinking about this problem and taking more notes.

No stupid question—this was the first lesson I learned at Chalmers. Compared to my undergraduate studies in China, I found that the interaction between professors, teaching assistants (TAs), and students at Chalmers was far more frequent and engaging. Here are three perspectives on why this difference feels so impactful to me:

The Structure of Teaching and Learning

During my undergraduate studies in China, my understanding of communication engineering often felt shallow. I might grasp the mathematical expression of a communication theory and solve exercises by referring to examples, but I rarely delved into the underlying logic or developed an intuitive grasp of the concepts. It was also difficult for me to articulate my confusion in an organized way. The role of a Teaching Assistant (TA) in China is quite different from that at Chalmers. During my undergraduate studies, TAs were usually responsible for grading assignments and exams, as well as calculating scores. If I had questions, I would typically go to the professor for help. Of course, for lab-based courses, TAs would also be present to guide students during the experiments.

At Chalmers, however, I could always find scheduled office hours to meet TAs in person or reach out to them via email for convenient discussions. As PhD students who had already taken these courses, they generally had a solid understanding of the material. To some extent, they may better understand where we might feel confused about the course content and engage with us in thorough discussions.

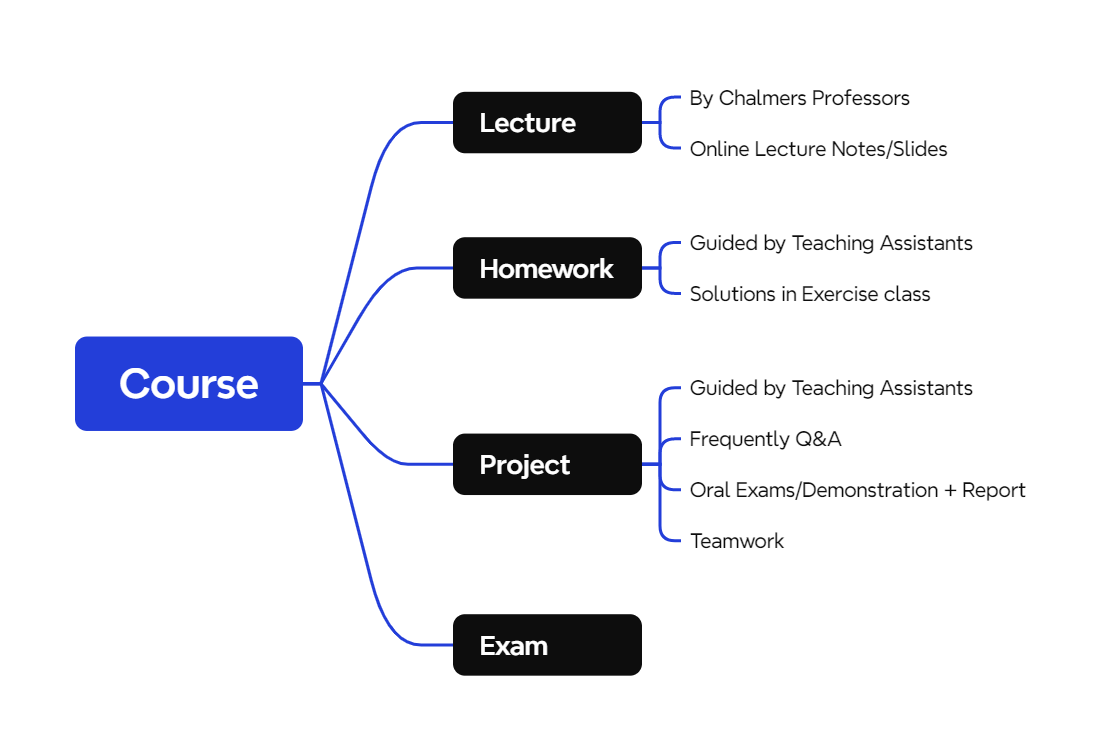

If you’re curious about the specific teaching setup of the Information and Communication Technology programme at Chalmers, you can refer to the following mind map. It clearly shows that the interaction between students and professors/TAs is ample, and the assessment methods are diverse, avoiding a single-track approach.

The Dual Nature of Knowledge

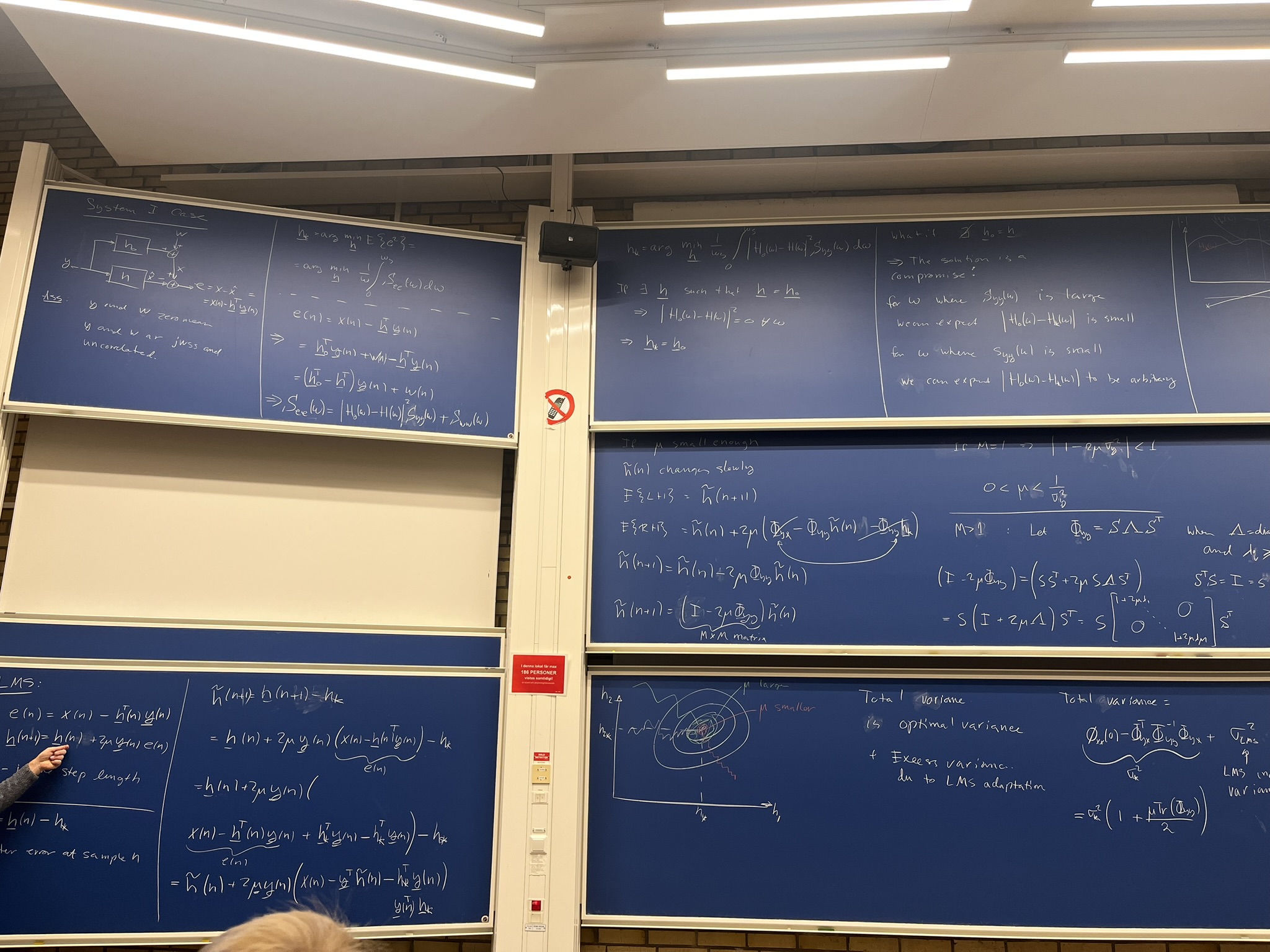

The philosophy of No stupid question lies in this: Professors, being deeply familiar with their subject, often operate on a higher conceptual level and may not naturally explore areas where stupid questions arise. However, through my time at Chalmers, I realized that so-called stupid questions are often fundamental questions. For example, one of the professors teaching Probability and Statistical Learning Using Python, Alexandre Graell I Amat, discussed the trade-off between model flexibility and overfitting in optimization problems—a classic yet essential issue. Similarly, in the Applied Signal Processing course, Tomas McKelvey illustrated the derivation of optimal filters using practical examples, emphasizing their foundational importance.

Mikhael Gromov’s words from his paper Stability and Pinching capture this duality beautifully (and though he was speaking about mathematics, I think the idea applies equally well to engineering sciences):

This common and unfortunate fact of the lack of an adequate presentation of basic ideas and motivations of almost any mathematical theory is, probably, due to the binary nature of mathematical perception: either you have no inkling of an idea or, once you have understood it, this very idea appears so embarrassingly obvious that you feel reluctant to say it aloud; moreover, once your mind switches from the state of darkness to the light, all memory of the dark state is erased and it becomes impossible to conceive the existence of another mind for which idea appears nonobvious.

There often seems to be no middle ground between “suddenly understanding everything” and “understanding nothing.” Teachers may find it hard to return to the transitional state of learning and identify with beginners’ perspectives. It’s only when I identify my own questions and engage in discussions with professors that I gain deeper insights—insights that cannot be fully grasped just by following a lecture.

From this perspective, Chalmers has taught me that asking questions is a form of innovative thinking. By approaching a problem from a unique angle, one moves beyond simply following the lecturer’s thoughts, leading to both confusion and progress.

The Motivation-Driven Teaching Style

For me, learning something new is a bit like exploring the streets of a foreign city—like Gothenburg, where I am now. A good motivation-driven course doesn’t start by asking you to memorize a map. Instead, it asks, “Where do you want to go?” and takes you there for a walk. The next time I explore, I can rely on my own abilities to find my way.

Probability and Statistical Learning Using Python, the professor Giuseppe Durisi, who is also our programme director, often connected theoretical concepts with tangible examples, such as rolling dice, drawing lottery tickets, or vending machines. Regardless of how complex the models or theories became, there was always a clear example anchoring our understanding.

This approach helped me engage more actively in lectures. When professors ask, “Any questions?” I now think critically and voice my doubts about specific parts of their presentation. Occasionally, I’ve even identified gaps or overlooked points in the lecture. These moments feel exciting for both me and the professor, deepen my understanding, and improve my focus in class.

If you come to Chalmers, Just Ask a Question! It’s the best way to embrace active learning and reflects the curious and engineering-driven spirit of Chalmers students.